Introduction

Welcome back to another installment of Semgrep’s protocol guides for busy security engineers! This time, we’re diving into the Agent to Agent (A2A) protocol, which has emerged as the dominant standard for how agentic software will interoperate. If your organization builds or consumes agentic workloads, a good working knowledge of A2A will serve you well in the coming months.

What is A2A?

A communication standard for LLM agents to talk to other LLM agents. While there is no industry standard definition yet, an “agent” is generally understood to mean a task-focused software application with one or more LLMs acting as a reasoning core along with a suite of tools allowing the LLM to perform actions in service of its mandate.

What is A2A for?

Enabling an agent to communicate with other agents in a standard way to facilitate black-box interoperability. Google’s canonical example is a travel agent when asked to "plan a trip to Tokyo". This agent will coordinate with an airline agent to book the flight. The agent will also coordinate with a hotel agent to book lodging. The original prompt may have asked for an outcome, and the agent orchestrates this work with other agents to achieve a coordinated result.

Why do we need the A2A protocol?

Orchestration works better when LLMs have smaller, specific tasks. Atomic tasks also enable task-specific tuning of models, without needing to be concerned about impacting other tasks. Most importantly, without standards, every agent-to-agent connection is bespoke glue code. Adopting a standard lowers the ongoing cost of understanding how agents interoperate, allowing us to be more effective at reviewing unfamiliar code.

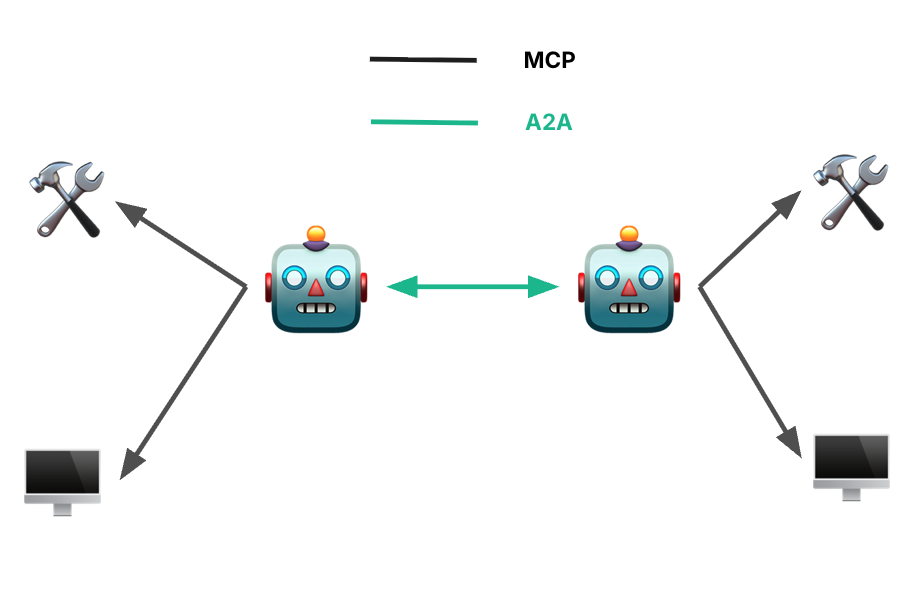

Does A2A compete with MCP?

No. MCP (Anthropic, Nov 2024) is agent-to-tool. A2A is agent-to-agent (Google, April 2025).

The goal of MCP was the creation of an agent that can gather context from tools and APIs to inform the model. By contrast, A2A defines the protocol for agent-to-agent communication, not agent-to-LLM communication. It is the coordination between independent agents.

In the travel example, the flight agent may use MCP to call a booking API, but A2A is how that agent shares its results with the overall travel agent.

Testing A2A Implementations

The A2A protocol has explicit bindings for JSON-RPC, gRPC, and JSON over REST. Custom bindings are allowed as long as you fulfill the binding requirements. For our purposes, it’s generally easiest to think about them in terms of the JSON-RPC objects: this is the most uniform format you will encounter them in, and protobuf schemas are “similar enough” that you should be able to do the translation with minimal cognitive load.

Core abstractions

Agent Card: a JSON object describing the agent’s capabilities, skills, auth schemes, endpoints, etc.

Task: The core unit of work for the protocol. Tasks are stateful (e.g. submitted, working, input-required, completed, failed).

Artifact: The output from task execution: effectively the “terminal state” of an agent Task.

Message: The atomic unit of communication for the protocol. Associated with a context and may be associated with a task. Clients may provide a context ID if they know it, servers must provide a context ID.

Here is a sample agent card:

{

"name": "booking-agent",

"url": "https://agent.example.com",

"skills": [{"id": "book-flight", "name": "Flight Booking"}],

"authentication": {"schemes": ["oauth2"]}

}

Generally speaking, Message objects are sent by clients and the server responds with Task objects. Even when soliciting more information (such as clarifying input), servers will generally prefer returning a Task in the appropriate state (`input-required`) with a Message component.

Here’s an example of this case from the protocol specification:

{

"task": {

"id": "task-uuid",

"status": {

"state": "input-required",

"message": {

"role": "agent",

"parts": [{"text": "I need more details. Where would you like to fly from and to?"}]

}

}

}

}

A2A supports the following transports in the specification:

Operations must return immediately: blocking is not allowed. Improperly blocking a request after receiving a message input seems like a potentially interesting area for implementation bugs in early deployments.

Long-running async task updates that aren’t over a server-sent event stream go to webhooks. It will be worth watching what happens when implementations allow injection of task updates to arbitrary targets.

What about the Agent Communication Protocol (ACP)?

IBM's Agent Communication Protocol merged into A2A in August 2025 under Linux Foundation governance. It is mentioned here as a competing standard for posterity.

Security Points of Interest

JSON-RPC and gRPC are well-understood transport mechanisms for both defenders and attackers. Due to the agent card, endpoints will be trivially discoverable on your domain(s), and adversaries will have some idea of how to approach them from attacking webapps for the last 20 years. Since the expected user is an LLM, attackers will bet (sometimes correctly) that prompt injection mitigations are minimal or not present.

Fortunately, we as an industry have experience building HTTP APIs, and many implementations will treat input as untrusted.

If implementations do not treat input as untrusted, the attack approach is straightforward: identify A2A endpoints, run existing tools that check for common jailbreaks, and see what works. Potential outcomes include unauthorized LLM compute usage, data leakage, or result manipulation.

Where is the attack surface?

Implementation of the executor

Most mistakes will likely end up here as business logic errors in the code that processes tasks and invokes LLMs. It’s somewhat trite to raise “just solve business logic errors, everyone!” as a risk, but traditionally, users needed some level of expertise or access to tooling to exploit business logic issues at scale. In this context, all of your users are technically capable and operate at inhuman speeds.

SDKs

We anticipate problems with object handling, serialization edge cases, and language-specific issues early on, decaying quickly to a long tail as researchers ferret out easily fuzzable mistakes. Due diligence when selecting an SDK will pay dividends.

The usual LLM input problems

Any LLM application will need to be wary of prompt injection, and the task-driven nature of an agent makes it highly likely you will inherit a significant amount of MCP attack surface as well.

Protocol-level issues

Unsigned Agent Cards

A2A (v0.3+) supports but does not enforce Agent Card signing. This allows spoofing by bad actors. Since there is no central registry for Agent Cards and spoofing is inexpensive, we expect this to join the rest of the internet background radiation of low-effort exploits.

Inadequate OAuth Controls

Recent academic work identifies some structural issues with early OAuth implementations that are worth keeping in mind:

Token lifetime: A2A doesn't enforce short-lived tokens. Leaked OAuth tokens can remain valid for extended periods. Combining this with stream forking could be Very Bad.

Coarse-grained scopes: Tokens that have broader capabilities such as a payment token aren't limited to single transactions, meaning it could be abused for accessing other unrelated resources.

Missing consent mechanisms: No protocol-level requirement for user approval before sharing sensitive data between agents - if an agent knows it, it can decide to send it wherever it wants.

Authorization is implementation-defined: To be clear - this is not the protocol’s job! Requiring authorization as part of the protocol is really all they can do. Make sure you understand how your authorization model applies to an agentic user before you start building.

Stream hijacking

The protocol allows serving multiple concurrent streams without mandating termination of other streams. This could allow a stolen or forged session token to silently listen in on a victim stream. A difficult bar to clear, but a desirable post-exploitation primitive if achievable.

Data leakage

Sensitive data (payment credentials, identity docs) may traverse intermediate agents, or exist in a shared agent context. Using a capability-based authorization scheme here will probably be a wise early investment.

Serialization

A2A uses JSON-RPC 2.0. The usual JSON attack surface applies: Unicode normalization, nested object depth, oversized payloads, dynamic type handling. Given that serialization has recently re-entered the wider security consciousness, it would be wise to remain mindful of this attack vector.

A2A Audit Checklist

Our MCP checklist spreadsheet was pretty popular, so we put together another one for auditing A2A protocol implementations.

Closing Thoughts

Given the difficulty of securing LLM behavior (and the recommendations of the specification itself) I believe we are going to see a revival in capability-based access controls. LLMs are, for better or worse, human-like users. They are the Confused Deputy Problem, personified. Capability based access, in a nutshell, is based around handles to resources: you open a file, that gives you a capability for that file, nothing more, if you are allowed that capability. You cannot confuse a deputy in a well-built capability system, because it does not matter what the deputy asks for. The resources themselves are “aware” of who has access to them.

Furthermore, it seems to me that A2A likely benefits aggregators and foundation model providers more than individual SaaS applications. The current population of deployments large enough to genuinely benefit from agent-to-agent protocols seems limited, though this is a poor indicator of future adoption: projecting growth in the “vibe coding” era continues to be challenging! Right now, there are not a lot of production A2A implementations. Given the excitement around agentic workflows and projects such as Gitlab Duo announcing intentions to support it in the near future, this will surely change. Security professionals have an opportunity here to get ahead of the security implications of widespread A2A adoption. We should take advantage of it.

Further Reading